I haven’t usually made a big deal of Black History Month. That’s because I feel Black history should be acknowledged year-round, routinely taught in schools, and understood by all Americans.

But in the context of efforts to erase African American history in National Park Service sites, including recent new ones in Philadelphia, and snubs like President Trump’s unwillingness to attend an MLK Day event, and his appalling unapologetic sharing of a video depicting the Obamas as apes, I value the month much more.

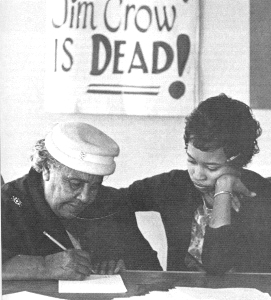

One aspect of African American history we should appreciate is the centuries-long effort to attain civil rights. While that’s a massive topic, today I’ll focus on the Black civil rights movement during the mid-1950s through the mid-1960s

The Problems African Americans Faced Mid-century

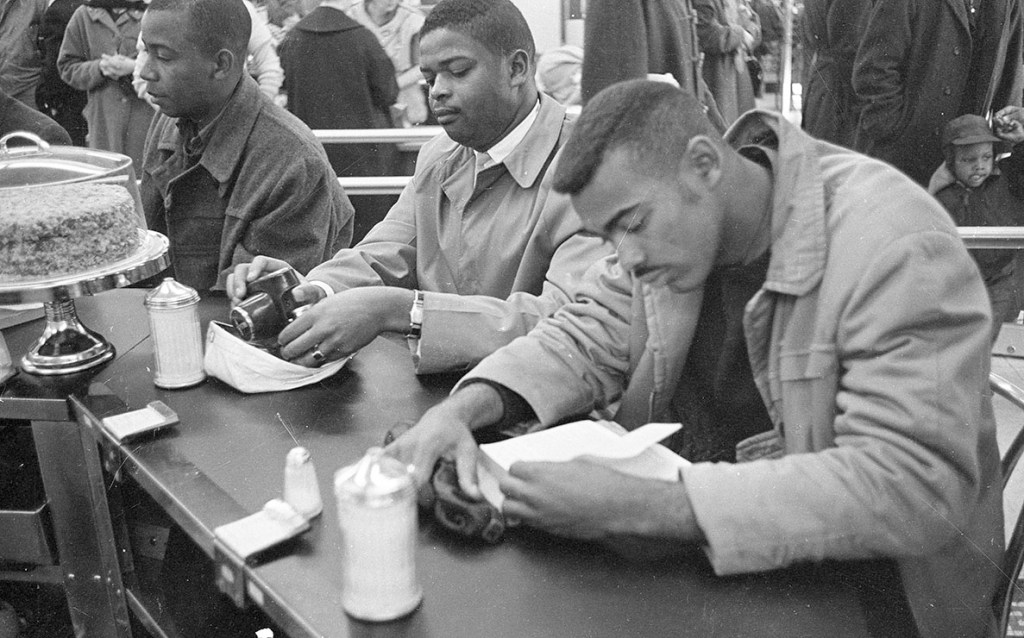

In the South in the early 1960s, African Americans faced segregation everywhere – not just most schools, but in restaurants, transportation, recreation (pools, parks, leagues), courtrooms, restrooms and water fountains, movie theatres, hotels, etc.

Segregation was decreed by state laws as well as a matter of etiquette enforced by whites. It was as though many white Southerners thought African Americans had cooties. The intent was to stigmatize, keep Blacks in a subordinate place, and to keep the races separate so that whites wouldn’t befriend, ally with, and love their fellow neighbors and citizens.

Blacks were expected to respect whites and show deference to them. The cumulative effect of these laws and practices was feelings of embarrassment, frustration, powerlessness, and anger.

Besides an end to segregation, African Americans wanted fairer economic opportunities. The norm was for there to be “colored” jobs (low-paying menial ones, especially those serving whites, with no possibility of advancement), and other jobs were reserved for whites. Want ads and traditions made that clear. Blacks who had advanced degrees had difficulty finding positions commensurate with their education.

Southern states made it challenging for African Americans to vote. They did this through a variety of mechanisms including literacy or understanding tests and even all-white primaries in some states. In 1962, only 26.8% of eligible Blacks in the South were registered to vote. The situation was better in Southern cities and worse in the Deep South, where only 5.3% were registered. (See Sitkoff, The Struggle for Black Equality, 110-111.) Blacks didn’t trust the criminal justice system – especially when they were systematically kept off juries.

Civil Rights Movement Strategies

Changing these conditions would take courageous, strategic, and very persistent efforts.

I would hate for people to think that it just took a few marches here and there, a few sit-ins, and speeches like King’s “I Have a Dream” to magically or quickly create change.

The variety of methods activists used was impressive:

- Legal efforts (e.g., The NAACP challenged state segregation laws starting in the 1930s, chipping away at them, eventually making it to the Supreme Court in cases like the Brown v. Board of Education decision)

- Voter registration drives – going door to door trying to persuade people it was worth the hassle and potential danger to try to get the right to vote

- Boycotts (e.g., Montgomery buses)

- Sit-ins

- Demonstrations like marches

- Civil disobedience (intentionally and peacefully breaking laws they believed were unjust, and accepting arrest and punishment)

- Freedom Rides (testing the federal law that said interstate buses and waiting rooms couldn’t be segregated)

- Lobbying and negotiating with politicians

- Creating a nondiscriminatory interracial political party in Mississippi to challenge all-white primaries and pressure the national Democratic Party at its 1964 convention

- Freedom Schools – to provide education, including about Black history, to kids in the summer.

These methods had to be used over and over in place after place that had the same problems.

The methods were led by Black activists who sometimes were joined or supported by white allies. Activists never knew whether their efforts would eventually lead to progress or just to frustration or punishment.

Opposition to Civil Rights

Since many of these efforts took place over 60 years ago, it’s not surprising that many of my students didn’t know about the types and intensity of the opposition that activists encountered.

One of the things that made change difficult was that white authorities – people with local and state power – resisted civil rights.

For example, white voter registration officials sometimes arbitrarily changed procedures, the hours offices were open, and/or made Blacks wait for hours. Since all power was in their hands, they could just decree that an applicant didn’t pass a literacy test or correctly interpret state laws. In a none-too-veiled threat, they might ask who an applicant worked for.

Fannie Lou Hamer learned first-hand the difficulty of being able to vote. The child of a poor sharecropper in rural Mississippi, Hamer didn’t even know until 1962, when she was 45 years old, that Black people could register to vote. She was arrested while attempting to register, and when she was released from jail, her employer ordered her to leave the plantation unless she withdrew her application to vote. Undaunted, Hamer even decided to try to register others. She was arrested for this work, and prison officials forced black inmates to severely beat her, which resulted in her suffering permanent injuries. Similarly, a local police chief used an electric cattle prod on someone canvassing for voters in Alabama. (Sitkoff, 112)

Besides arresting activists (often unjustly), police sometimes harassed them. When I was reading the records of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee from the early 1960s, activists in small towns reported how scared they were due to being followed by tailgating police. Some were regularly ticketed for trumped up traffic offenses. A police officer threw a stone through the window of Montgomery bus boycott organizer Jo Ann Robinson and another poured acid on her car.

Black men driving private taxis during the boycott in Montgomery in 1955 no longer could get insurance for their vehicles. Encouraging resistance, the mayor publicly joined the White Citizens’ Council, an influential white supremacy group.

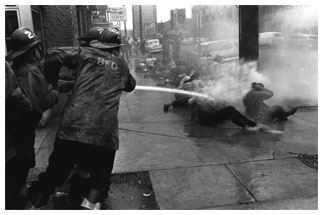

Sometimes the police conveniently disappeared so that mobs could attack activists, such as with the Freedom Rides. Sometimes city officials refused permits for demonstrations. When activists in Birmingham marched anyway, police chief “Bull” Connor set dogs and high-powered fire hoses on them.

Laws were enforced selectively. King and 88 others were arrested for organizing a boycott because officials found an obscure Alabama anti-conspiracy law prohibiting conspiring to interfere with a business. He had to pay a $500 fine if he didn’t want to spend a year in jail.

On the other hand, in 1963 Governor George Wallace refused to comply with the 1954 Supreme Court ruling that prohibited segregation in education. Rather than allow the desegregation of the University of Alabama, he dramatically blocked the entry of 2 Black students who had enrolled.

Similarly, for ten years, the state of Virginia adopted a policy of “massive resistance” after the Brown v. Board decision, and actually closed the doors of public schools in a number of counties and cities rather than allow Black students.

When the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed segregation in all public accommodations, many municipalities found ways to bypass the law. Ways to avoid integrating swimming pools included closing the pools or else selling them so they would be turned into private membership clubs which could deny entry to whoever they pleased. For example, after Washington, D.C. ended the segregation of pools in 1953, 125 new private swim clubs were opened within ten years.

Such opposition from powerful city and state officials disheartened all who wanted equality.

Harassment and Violence from White Individuals

Threats and intimidation from private citizens supplemented the opposition from civil authorities. For example, Martin Luther King’s phone rang constantly with death threats during the Montgomery bus boycott, and he estimated that he received 40 hate letters a day. Klansmen drove through Black neighborhoods, sometimes shooting into people’s windows, sometimes burning crosses.

During the Freedom Rides in 1961, a mob of about 50 people led by KKK members armed with baseball bats, metal pipes, and chains met the Trailways bus carrying the interracial group of riders in Anniston, Alabama, and smashed windows and dented the sides of the bus. After the police eventually came and accompanied them outside city limits, someone threw a firebomb through a broken window while others tried to barricade the door and trap the riders. When they escaped the bus, the mob severely beat some of them.

Six days later, a mob also waited in Montgomery. As the bus pulled up, the driver opened the door and said, “Well, boys, here they are. I brought you some niggers and nigger-lovers.” After the mob attacked, a 61-year-old rider was left close to death, John Lewis got a concussion from being hit with a wooden crate, and a bleeding James Zwerg suffered spinal injuries and got no medical treatment for 2 hours. Even a federal agent who tried to stop the mob was knocked unconscious. (See Sitkoff, 94-95)

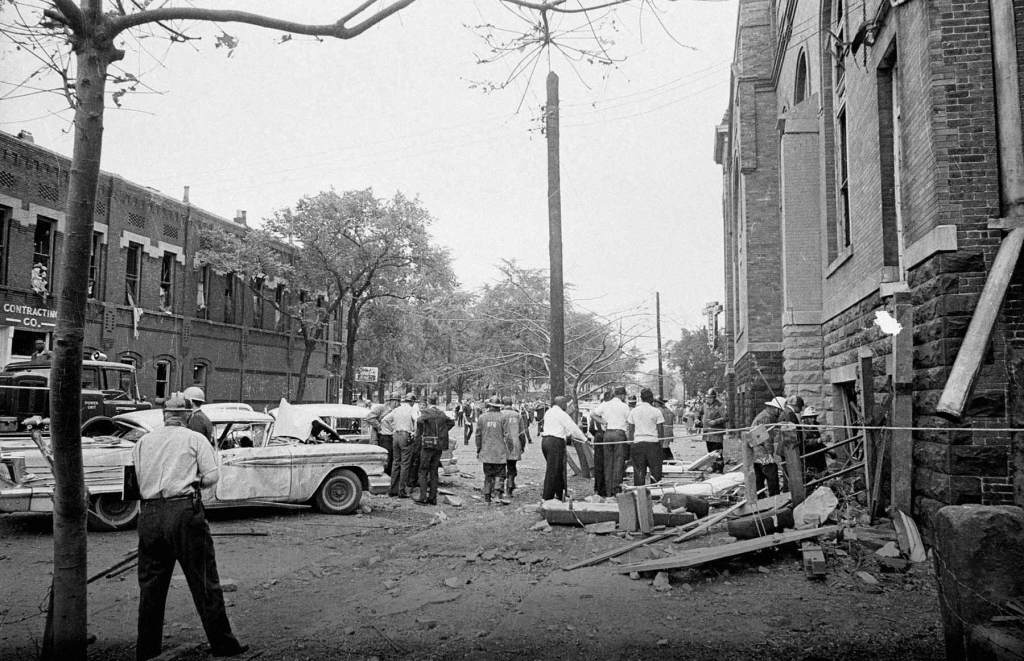

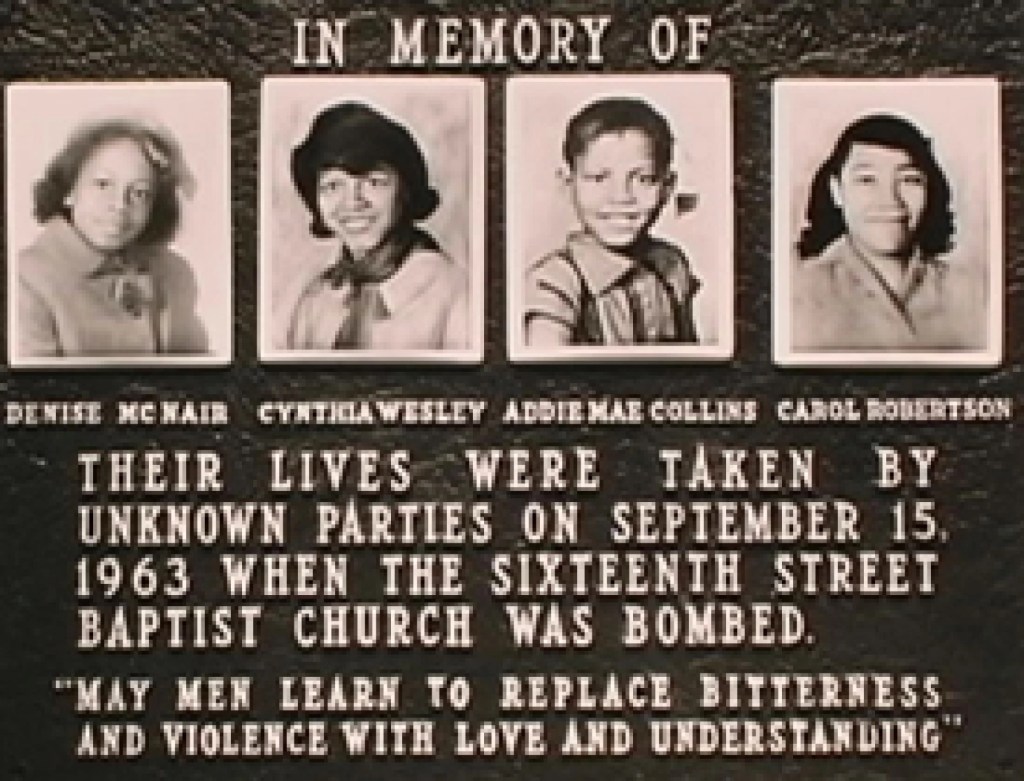

In Birmingham in 1963, the 16th Street Baptist Church was bombed right before the start of Sunday service, killing four girls, Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Carol Denise McNair.

During Mississippi Freedom Summer 1963, historian Harvard Sitkoff reports (in The Struggle for Black Equality) the following incidents of opposition to the movement:

- 30 homes bombed

- 35 churches burned

- 80 people assaulted

- 30 people shot at

- 6 murders. This included when Michael Schwerner, James Chaney, and Andrew Goodman were investigating the burning of a church in Philadelphia, Mississippi, where a deputy arrested them for speeding, and then intentionally released them to Klan members, who killed them. An FBI webpage currently celebrates the federal government’s role in finding the bodies and the perpetrators.

Medgar Evers, army veteran and NAACP leader, was assassinated by Klansman Byron De La Beckwith, who despite being arrested a few years later, wasn’t convicted of the murder until 1994.

James Meredith, first Black student admitted to the University of Mississippi, was shot during a March Against Fear in 1966.

There were many other martyrs for the movement, many of whose names are not well known.

Martin Luther King, Jr., the most influential advocate of nonviolence, was assassinated in 1968.

It is simultaneously inspiring and daunting to realize how many people courageously dedicated their efforts so that our nation could attain civil rights for all its citizens.

Those on the front lines risked arrest, harassment, physical pain, economic repercussions, and even their lives. However, there was a role for anyone who was concerned about inequality.

Leaders strategized about which methods might work and how to gain attention and sympathy from the nation. Civil rights groups organized and raised funds necessary for defending the activists and challenging unjust laws and practices. Community members sustained the spirits of one another. Allies sent money and communicated with elected representatives about the need for legislative action and enforcement of laws.

All these actions are worth remembering.

Some facts for this post came from Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (Harvard University Press) and Harvard Sitkoff, The Struggle for Black Equality (Hill and Wang).